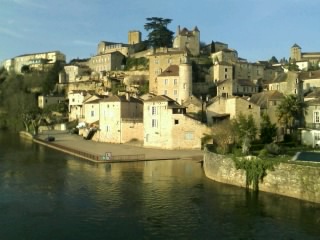

Puy l’Eveque on a beautiful Spring evening

I’ve always liked Puy L’Eveque. It’s much nicer than its more famous cheesy cousin Pont L’Eveque, and – having gone downhill for years – it’s now showing signs of having a return to its quiet elegance.

You may think its ability to serve up high quality fish n chips and Hamburgers Americans would kill for is a retrograde step, but it isn’t: more accurately, it is yet another way in which French cooking has inspired Brit immigrants to show how national dishes need not be junk…and in so doing, are revising the younger French generation’s view of that food. Equally, comfortable old eateries catering for ageing roués like me are still there unchanged by fashion, while new brasserie grillades with their own unique ambience (created by independent owners, not controlling chain marketing suits) are popping up here and there.

It’s when I potter around the myriad Puy L’Eveques of France that I find myself wishing I’d come to the Lot valley 25 years ago and actually written the definitive fin de siècle 20th century novel, rather than just wittering on about it. Or failing that, troughed my way to an early grave by penning a guide to all those little-feted eateries nevertheless beloved of the locals. I did at one point have a half-decent title for it – Unsung Suppers – but like so many projects of one’s middle years, it was floated one summer’s evening at an outside table in some Cypriot hideaway, only to float away later on a calm sea of Arsinoe.

⇔⇔⇔⇔⇔⇔⇔⇔

This morning, I chose to dodge the town centre and motor back home along the south of the Lot river, on the wonderful old D8. It cuts a meandering, gentle swathe right through the heart of some of Cahors’ finest domaines. It is my largely untutored but firm belief that Cahors vines have a DNA up there (albeit in a different way) with the very best that the Cotes D’Or can offer….and the resultant reds retail at a fraction of Northern wine prices.

The firmness of my belief is directly correlated with the many years of selfless quantitative experience I have personally donated to the study of the complete range of Cahors output.

As you head south away from Burgundies, Rhones and Loires, there is still far too much chance of coming up against classic British Claret snobbery. Setting aside the obvious fact that the term ‘claret’ itself is based on a wine that wasn’t even red, this kind of affected savoir faire is often ignorant of the rarely retold real history of how the fame of Bordeaux wines developed.

250 years ago, the Cahors growers shipped their excess production via barge along the Lot and then up the Garonne for (variously) blending and export. Human curiosity being what it is – incurable – Bordeaux viniculteurs began sampling the barrels that arrived in their main port. They quickly reached the conclusion that the contents were superior to their own efforts.

All the claret vines growing today are based on cuttings and grafts bought from Cahors growers. But that’s not the end of poking holes in inflated reputations.

The great phylloxera epidemic that devastated French vines (especially those producing whites) after 1855 was only stopped by the mass import of Californian vines that were resistant to the insect’s grubs.

Phylloxera also attacked several varieties of Spanish vine developed for fortification into sherry. For reasons still unclear to crop geneticists, the Cypriot sherry vines were immune…so they too were imported en masse, and saved the Spanish Jerez industry.

In the early 1970s, the EEC as was passed a blatantly protectionist law declaring that only Spanish sherry could use the generic descriptor. This stopped Sherry’s saviour, Cyprus, from being allowed to describe its output as sherry. Things could only get worse once Cyprus joined the EU…and so indeed it has proved.