An encounter with Bob the Bouncing Czech

Welcome to the first in a new series. I’m creating a new page at The Slog allowing me to enjoy some R&R – while hopefully at the same time entertaining Sloggers with some of the more bizarre experiences I’ve had as an advertising strategist and general all-round oddball.

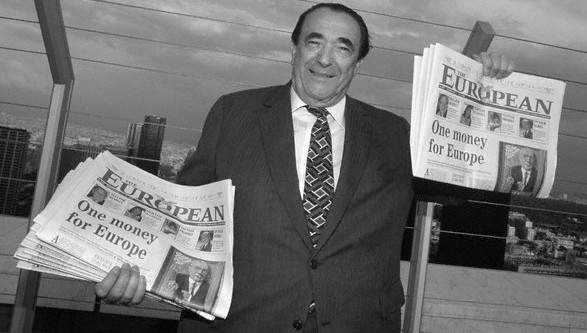

Robert Maxwell was an incorrigible monster who took over and ran many newspapers – usually into the ground. The European was one of the few titles he launched (in 1990) and at that time I was the Deputy Chairman of a large London-based ad agency called Bates.

Being Czech by birth, Maxwell was a great EU enthusiast. No amount of reality intrusion could dissuade him from his view that everyone was just dying to read a newspaper about a non-existent country called Europe. Indeed, you can judge Bob’s insight for commercial success from the headlines in the shot above. They are from the launch edition, and they call for ‘One Money for Europe’. He got his wish posthumously. The rest of us are still alive, and dealing with the consequences.

One winter mid-afternoon, I got an internal call from my Chairman to say that we’d been summoned into the Maxwellian presence that evening. At 6.30 pm, the chauffeur took us to Maxwell House (yes, it really was called that) where his flagship tabloid the Daily Mirror was then housed. With surprising promptness, we were ushered into his private quarters by a retainer, and there we waited as Robert Maxwell continued a multi-directional set of conversations on phones of varying colours from a place we could not see, only hear.

Across from where I sat was an enormous wardrobe. It was enormous mainly because Maxwell was an enormous bloke. I doubt if I have even seen a man since who was quite so wide and tall at the same time. Inside one of the wardrobe doors hung a series of baseball caps, all of which said ‘Cap’n Bob’ on the front. Given this was Private Eye’s mischievous nickname for the tycoon, I was surprised he’d adopted it. But then, on all four walls of this room were originals of umpteen cartoons about him – every last one of which was critical of its subject.

Eventually, we were led up to the higher level of a small office hidden around one corner of Maxwell’s personal space. He was still on the phone, taking a call from one of his editors about a Princess Margaret story. Even hearing only half of the conversation, it was obvious that the Queen’s sister had scalded herself after falling pissed into a very hot bath. Maxwell said simply, “Spike it”, and slammed down the receiver. This was dramatic stuff.

Maxwell explained that he wanted “a jolly good fine old English agency like Dorland” to launch his new pan-European organ. We were by then not called Dorland at all, but it seemed churlish to interrupt the great man in full flow. Having fired a few inconsequential questions at my boss, he turned to me and asked “What dooo yooo dooo?”

Although an affected Englishman, Maxwell talked in this strangely sonorous tone during all the occasions when I met him over the ensuing weeks. I began to explain my arcane strategic function, but after about four seconds he lost interest and picked up another phone. He asked his pa to get hold of an extremely famous journalist of the day. After a few minutes, the hack came back to him, at which point Maxwell dictated to the unfortunate personvarious fictitious versions of recent events for use as Opeds. Shortly after the Big Yin fell off his yacht eighteen months later, I was greatly amused to hear an interview with this journalist, in which Robert Maxwell was described as “an excellent proprietor who never interfered with editorial policy in any way”.

During the ensuing months, we produced a range of TV commercials and poster ads for the launch. The paper was a White Elephant from Day One ( they didn’t hide invisibly in rooms in those days) although it did outlive its inventor. Somewhat predictably, we never got paid.